Articles

How Domestic Producers are Coping with Lower Oil Prices

By G. Cook Jordan, Jr. and C. Hutch Greaves

The behavior of oil prices in 2018 has been a reminder that oil markets are seldom predictable. According to The U.S. Energy Information Administration crude oil spot price data, West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude started the year cents above $60 per barrel, rallied to a four-year high of $77 per barrel by late June, hit $76.40 on October 3rd, before embarking on a steady descent that has seen WTI average daily losses of nearly $0.38 per barrel per day en route to a closing price of $51.07 on December 10th. To put this pivot into context, prices entered a bear market on November 8th just five weeks after reaching a near four-year high on October 3rd, and have fallen approximately 16% since then.

These price gains were underpinned by three factors. First, pipeline bottlenecks in U.S. shale-producing regions, primarily the Permian Basin in West Texas, intensified in the wake of record domestic production that saw the United States usurp its foreign counterparts to become the world’s largest crude oil producer. Second, the Trump Administration withdrew from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) with Iran which, in tandem with plummeting Venezuelan production and stumbling numbers from other OPEC stalwarts like Angola, provoked fears of global supply shortages. The third factor supporting price gains was strong economic growth in the U.S. In October, these upward pressures were unseated by global oversupply and a retrenchment in global economic growth, triggering the plunge.

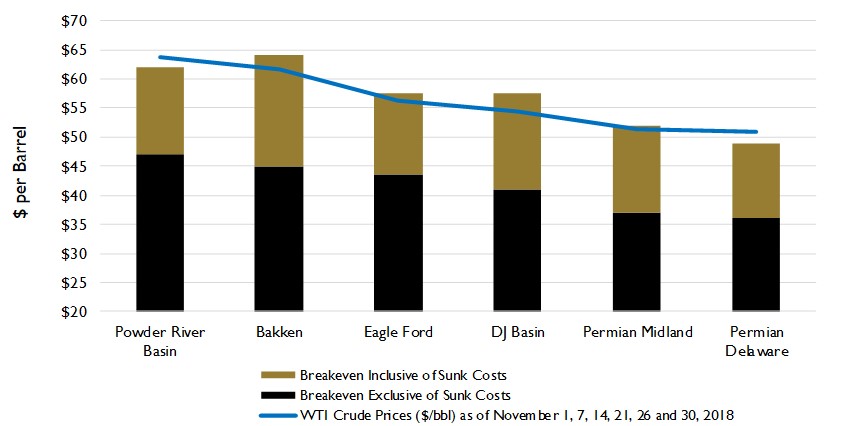

One particular group that finds this market pivot unwelcome is domestic producers, who throughout the year had, on aggregate, produced world-beating quantities of oil in a price environment reminiscent of that which they enjoyed pre-2014. Interestingly though, many operators claim the ability to make a profit, even when prices are around $50 per barrel. Per The Wall Street Journal (WSJ), “…companies… have promised that they have thousands of wells that they can drill profitably even at $40 per barrel. Some have even said they can generate returns on investment of 30%.” Eyebrows naturally raise at such an assertion given that during 2017, when prices averaged about $50 per barrel, profits averaged 1.3% of revenue. This misalignment, WSJ states, is rooted in the fact that operators base such claims on a metric called breakeven, defined as “…the selling price frackers need to generate a small profit on individual wells or projects.” The breakeven metric doesn’t account for sunk costs, or costs which have already been expended (land, overhead, infrastructure, etc.), because such costs are irrelevant to the decision to undertake the drilling of a new well because they’ve already been deployed. Hence the profit discrepancy between their verbal and corporate statements, as the corporate bottom line does account for these costs.

In assessing the claims of domestic operators amidst this new price environment, consider Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 – Oil Production Breakeven Points vs. November Oil Prices

Source: R.S. Energy Group / WSJ.

While an OPEC production cut, which may be on the horizon, would certainly benefit domestic producers who only recently saw higher prices manifest in their bottom lines, it would be short-sighted to discount their ingenuity in finding ways to operate profitably at today’s price level. Throughout the 2015 to 2017 time period, oil prices fluctuated within the $30 per barrel and $60 per barrel range, prompting the industry to invest heavily in a quest for operational efficiencies that would enhance their resilience to low prices.

The industry first targeted big-data analytics, which delivered long-overdue efficiencies through implementing end-to-end digitalization of field operations. The use of sensors, robotics, control systems, and analytic insights drive cost-savings and higher margins through intelligent maintenance, workflow automation, improved labor utilization, etc.

A second source of largely unrealized efficiency gains concerns wastewater treatment. Water is both an input to, and an output of, the hydraulic fracturing (fracking) process, and the ratio of produced water to produced hydrocarbons ranges, on average, from four-to-one to ten-to-one. For perspective, in producing an average of 3.6 million barrels per day of oil in November, the Permian Basin alone produced approximately 14 to 36 million barrels of wastewater every day. The produced water is riddled with toxins that mandate a complex treatment and disposal process, historically involving truck transportation to a remote treatment facility, treatment, and disposal in an injection well. This process accounts for a staggering 25% of a well’s lease operating expense in the Permian Basin, even before considering estimates that the combination of surging production and the trucking shortage could inflate the cost of production by $6 per barrel, according to WSJ.

Recognizing this inefficiency, capital has flocked to the aid of operators via financing for private wastewater treatment companies. A subset of these companies has provided a short-term solution through constructing pipelines that connect producing regions with remote treatment facilities, streamlining wastewater transportation through improving volume capacity at a fraction of the cost of trucking. It is a short-term solution because it perpetuates the use of controversial injection wells. The long-term solution is technology that allows on-site treatment and recycling of wastewater. While this technology has existed for decades, it is hardly ubiquitous. Technological advancements in wastewater recycling, in conjunction with increasing social and regulatory pressure on injection wells, make improving recycling technology a major objective for domestic producers.

Ultimately, opinion is divided regarding the fitness of domestic operators to deliver consistent profits at the questionable $50 per barrel price level. According to a recent Reuters article, on one hand, “…The reality is a lot of them get scared at $50, and their banks get scared at $50.” The contrary outlook “…sees an industry just now poised to move out of its costly development phase and into…’harvesting mode,’ pulling profit from past investments.” We will stay tuned for further developments.

Sources:

“Shale’s Growing Profits at the Mercy of OPEC Cuts, Trump Tweets,” Reuters, December 10, 2018.

“Oil on Cusp of Bear Market as Supply Worries Persist,” MarketWatch, November 8, 2018.

“The Rise and Fall of Oil Prices in 2018,” Petroleum Economist, December 12, 2018.

“Not Your Father’s Oil and Gas Business,” Strategy&, PwC US, 2016.

“The Next Big Bet in Fracking: Water,” The Wall Street Journal, August 22, 2018.

“Fracking Water’s Dirty Secret—Recycling,” Scientific American, 2018.

“Big Fracking Profits at $50 a Barrel? Don’t Bet on It,” The Wall Street Journal, December 4, 2018.